By Roselyn Fauth

How can we make play even more fun..? was a question that we continued to ask our selves through out the planning and design of the playground project. It was clear, that finding a story that was special and local and bringing those themes into the play space was going to help make the area more visually appealing, inspire people to play with their imaginations and help to connect with our local stories and cultures.

Tuna Eels were a vital food for Māori, who caught them using weirs built on rivers, or with traps, nets, spears and bait. Large numbers of eels were captured on their yearly migrations to the sea. There used to be many tuna that lived at Waimataitai. This was a hāpua (lagoon) situated near the Tīmaru foreshore. It was renowned as an important source of mahinga kai. In 1880 Hoani Kāhu from Arowhenua described Waimātaitai as “e rauiri” (an eel weir) where tuna (eel) and inaka (whitebait) were gathered. This saltwater lagoon was eventually lost in 1933 when it was drained and turned into Ashbury Park. Today, a drain runs under the feild and connects the sea to the Waimataitai stream where tuna can be found. - kahurumanu.co.nz/atlas

We decided to shape our mound into a tuna eel and split it into three sections. Inspired by a Maori myth of the encounter between Maui and Tunarua, as he terms Tuna. We are told that Maui cut off the head of Tuna and cast it into the sea, where it became a koiro (conger eel); he threw the tail into fresh water, where it turned into a tuna or fresh water eel; the blood of Tuna was absorbed by such trees as rimu, totara and toatoa, and others that now have red heartwood. - nzetc.victoria.ac.nz

A Tribute to Tuna: Unique Eel-Themed Mound Enriches Caroline Bay Playground Experience

The picturesque playground at Caroline Bay has undergone a transformation that is sure to captivate the hearts and imaginations of children and adults alike. The newly designed playground boasts a centerpiece that pays homage to the cultural significance of the tuna eel, while also nurturing creativity, physical activity, and cultural understanding.

The volunteers behind the project, collectively known as CPlay, have chosen to incorporate an eel-themed mound into the playground for a multitude of compelling reasons. The choice is driven by the desire to create an environment that fosters a strong connection between children and the natural world, enhances playtime experiences, and honors the deep cultural importance of the tuna eel to the local Maori community.

The tuna eel-themed mound serves as a canvas for children's imaginative journeys. By crafting a landscape that resembles a tuna eel's form, CPlay aims to stimulate the young minds to explore and invent stories centered around the tuna eel's habitat, behaviors, and adventures, including its incredible journey to the Kermadec Trench for spawning.

Moreover, the mound's design holds educational value, as it introduces children to marine life and ecosystems. Through playful engagement with the eel-themed mound, children are inspired to learn more about the vital role tuna eels play in the ecosystem and the unique characteristics that make them extraordinary creatures. The playground becomes a classroom where children can absorb knowledge about the natural world through active play.

The interactive nature of the eel-shaped mound encourages physical activity, spatial awareness, and the development of gross motor skills. Complete with tunnels, bridges, slides, and various levels, the design invites children to climb, crawl, balance, and slide their way through an engaging and challenging play experience. This dynamic design transforms the traditional concept of a mound into a canvas for exploration and physical development.

The playground's eel theme extends beyond the mound itself, creating a themed play area that immerses children in an underwater world. Fish-shaped structures, seashell climbers, and other marine-inspired features enhance the atmosphere of imaginative play, turning every visit to the playground into an adventure beneath the waves.

However, the inspiration behind the eel-themed mound doesn't end with entertainment and education. CPlay's thoughtful design also seeks to deepen the playground's connection to local culture and heritage. The Maori community's reverence for the tuna eel, often seen as a taonga or treasure, is highlighted through the playground's design. The eel's role as a guardian spirit of water bodies in Maori mythology is acknowledged, fostering a cultural connection that encourages children and visitors to appreciate the rich heritage of the region.

By incorporating Maori tuna eel legends and stories into the playground's design, CPlay showcases the importance of eels to the local Maori community. Plaques and interactive panels provide opportunities for children and families to learn about the cultural significance of eels and their place in Maori traditions.

The eel-themed mound, along with its surrounding features, symbolizes the interconnectedness of nature, water, and land in Maori culture, emphasizing harmony and balance. Through collaboration with local Maori artists, storytellers, and educators, the playground design is enriched with authenticity, fostering a sense of pride and ownership within the local Maori community.

As children engage with the eel-themed playground through workshops, interactive play, and storytelling sessions, they not only experience holistic learning but also contribute to the preservation of Maori cultural heritage for generations to come. The playground becomes a space where imagination, education, and culture intertwine, creating an inclusive environment that welcomes children of all backgrounds.

The eel-themed mound at Caroline Bay's playground is more than just a play structure. It's a tribute to the past, a celebration of the present, and an investment in the future, where children learn, play, and honor the cultural treasures that define their community.

- Nature Rocker - It has springs underneith and rocks. 1.6 m. Designed to look like the stamens of a frangipani or hibiscous flower.

- Xylophone Cadenza and Caden - Notes arranged like a xylophone or glockenspiel, covering two octaves. Explore melody, harmony and rhythm. Alumium, Wood and Fiberglass.

- Congo Set - Rainbow Sambas Musical Instruments to shape a love of music, beat and rhythm. Smallest 550mm high to largest 850mm high.

- Interactive Bridge with Sound. 2m long with 6 bells. Almost anyone can move the bells and make a tune.

- 2 x Tunnels. Explore the tunnels, and learn to share and wait their turn. Made from rotational moulded plastic, so they won't overheat and are well supported to play on.

- 1500mm Double Slide. Race your friends to the bottom!

- Inground Trampolines. Bounce their way to happiness and good health! From stronger muscles and bones to better balance, coordination and motor skills, cardiovascular health, and improved concentration and focus.

- Inclusive Carousel. Takes a wheel chair, and can fit multiple people who can control their speed by rotating the turntable.

- Honeycombe Carousel. 1000mm diameter nest basket gently rotates.

- Wheel Chair Trampoline. Designed for wheelchair users. Along the small sides, the fall protection mat is slanted to create easy access for wheelchairs.

- Spinning Bucket. 600mm diameter bucket spinner for all ages and abilities - spin to your hearts content! Great for inclusive play with its clever and extra-safe design including: Higher back for backrest, Handgrips on the sides, and Lower at the front to make getting out easier.

Why we chose to theme this area around a tuna eel

- Stimulating Imagination: Children have vivid imaginations, and by incorporating imaginative elements like an tuna eel shaped mound, you can encourage them to create stories and scenarios that revolve around the eel's habitat, behavior, and adventures, including swimming to the Kermadec Trench to spawn.

- Educational Value: The tuna eel shape could serve as an educational tool to introduce kids to marine life and ecosystems. Children might become curious about eels, leading them to learn more about these creatures, their role in nature, and their characteristics. Maybe they will feel even more connected to this taonga treasure when they learn that Waimataitai lagoon used to be a massive eel weir.

- Interactive Play: An tuna eel shaped mound has tunnels, bridges, slides, and different levels that children can explore, promoting physical activity and spatial awareness. This interactive design could encourage climbing, crawling, balancing and sliding, contributing to their gross motor skills development.

- Themed Play Area: Themed playgrounds can be exciting and memorable for children. An tuna eel-shaped mound could be part of a larger underwater-themed play area, with other features like fish-shaped structures, seashell climbers, and more. This kind of environment can make playtime more engaging and immersive.

- Aesthetic Appeal: A creatively designed mound that resembles an tuna eel can add an element of aesthetic interest to the playground. It becomes more than just a mound; it becomes a piece of art that enhances the visual appeal of the space.

- Community Engagement: Unique and interesting playground designs can draw the attention of both children and adults, potentially increasing community engagement and promoting social interactions.

- Local Wildlife Connection: If the area has a local eel population or if eels are significant in the local culture or history, an eel-themed playground could help forge a connection between children and their natural surroundings.

- Inclusivity: A well-designed eel-shaped mound could provide opportunities for children with various abilities to engage in play, promoting inclusivity and ensuring that the playground is accessible to a wide range of children.

- Cultural Connection: Tuna Eels have deep cultural significance in Maori mythology and history. They are often associated with the guardian spirit, or kaitiaki, of water bodies. Creating an eel-themed playground could serve as a way to honor and connect with these cultural beliefs, helping children and visitors develop an appreciation for Maori heritage.

- Storytelling: Incorporating Maori tuna eel legends and stories into the playground design can serve as an educational opportunity. These stories could be displayed on plaques or interactive panels around the playground, allowing children and families to learn about the cultural importance of eels to the local Maori community.

- Symbolism: The eel's presence as a central theme could symbolize the interconnectedness of nature, water, and land in Maori culture. It could serve as a reminder of the harmony and balance that Maori tradition emphasizes.

- Community Engagement: Involving local Maori artists, storytellers, and educators in the design process can helped ensure that the eel-shaped mound accurately represents Maori culture and values. This engagement can foster a sense of pride and ownership within the local Maori community.

-

Educational Workshops: The playground could host workshops and events focused on sharing traditional Maori knowledge about eels, their lifecycle, their importance to the ecosystem, and their place in Maori traditions. These workshops could provide opportunities for cultural exchange and learning.

-

Inclusivity: Incorporating Maori cultural elements in the playground design can help create a sense of inclusivity, making Maori children and families feel welcome and acknowledged in the space.

-

Legacy and Preservation: By highlighting the cultural significance of eels, the playground can contribute to the preservation of Maori cultural heritage for future generations.

-

Holistic Learning: The eel-themed playground could be part of a larger educational initiative that includes environmental education, storytelling, and interactive play, providing a holistic learning experience for children.

Information about the Tuna

Mahika kai literally means 'to work the food' and relates to the traditional value of food resources and their ecosystems, as well as the practices involved in producing, procuring, and protecting these resources. LEFT Tuna (eel) on display at the South Canterbury Museum. RIGHT Mōkihi display at Te Ana Ngāi Tahu Māori Rock Art Centre.

The coastline was abundant in marine life and offered bountiful mahika kai (food resources) for local Māori. There was an abundance of fish and shellfish on the reefs, plenty of sea birds, eggs and seal pups on the coast and tuna (eels), waterfowl and freshwater fish in the estuaries and rivers. Tuna (eel) and inaka (whitebait) patete (fish), and kōareare (the edible rhizome of raupō/bullrushes) were also important staples of the area.

Travel by sea was common and much faster than travelling by land. Many settlements were within sight of each other and only hours away in settled weather by waka (canoe) or the double-hulled waka hunua. Trading of food and resources between villages up and down the coast was an important part of the economy. Pounamu (greenstone) and titi (sooty shearwaters /muttonbirds) were sent north to trade in return for kūmara, taro, stone and carvings.

Rivers were like highways inland. Tākata whenua (local people) foraged inland for weka, ducks, harakeke (flax), aruhe (fern root/bracken) and tī kōuka (cabbage tree) and lowland forests provided a wide range of timber and forest birds.

Southern Māori developed a special vessel to navigate the fast-flowing braided rivers: the mōkihi. Made from bundled raupō (bullrushes) or kōrari (the flower stakes of the harakeke flax bush). They were lightweight, sturdy and could be made on the spot to guide down the river carrying heavy loads. The largest mōkihi could carry up to half a tonne in weight.

It was a long trek from the coast to the inland lakes and mountains, but mōkihi could make the return journey in a single day. Because there was no way to bring them back up-river they were often used just once. If they were to cross a river, there were left in a dry spot for the next party to use.

Local Māori communities have faced massive changes over the past 150 years as a result of European settlement, including loss of traditional food resources especially as the coastline changed and the city expanded.

Frangapani detail to represent pacifica people, and the tuna eels journey to the Kermadec Trench, (submarine trench in the floor of the South Pacific Ocean) where the Tuna continue their life cycle to lay eggs.

The harbour coastal waters are of strong cultural value to Te Rūnanga O Ngāi Tahu. Te Rūnanga O Ngāi Tahu

Tuna - eel

Tuna is a generic Māori word for freshwater eels. Māori have over 100 names for eels.

They live: in lakes and rivers connected to the sea.

They eat: small insects larvae, snails, midges and crustaceans. As their mouths get bigger, they can eat kōura (freshwater crayfish), fish, small birds and rats. When scared they bite!

Did you know: they are the largest fish in Aotearoa freshwaters

There are three tuna eel species in NZ: The longfin eel, known as tuna, is one of the largest eels in the world.

LONGFIN EEL: (Anguilla dieffenbachii) Max size: 2m, 25kg

SHORTFIN EEL: (Anguilla australis) Max size: 1.1 metre, 3kg

AUSTRALIAN LONGFIN EEL: (Anguilla reinhardtii), Max size: 2 metres, 21kg

They are a taonga species: central to the identity and well being of many Māori and are a significant mahinga kai (food).

Traditional knowledge

Tuna is a generic Māori word for freshwater eels; however, but there are a multitude of names that relate variously to tribal origins, appearance, coloration, season of the year, eel size, eel behavior, locality, and capture method. Tuna are arguably one of the most important mahinga kai resources for Māori. They were abundant, easily caught, and highly nutritious. Tuna were especially important in southern New Zealand, where it was too cold to grow some crop foods. Some tuna were considered sacred, and on occasion large eels were fed and noted to be treated as gods.

Many methods were used to take tuna - a common method for capturing adult tuna was using baited hīnaki, while juvenile tuna were taken on their upstream migration in bunches of fern. Tuna were often stored live in large pots for later consumption or hung to dry.

Tuna or freshwater eels are a very significant, widely-valued, heavily-exploited, culturally iconic mahinga kai resource. Although there are many stories and legends of tuna spawning in freshwater, what is certain is that all freshwater eels spawn at sea. Adult freshwater (living in streams, lakes, wetlands) can live up to 100 year old. They feed on insects, snails, fish, and even birds. Female tuna can reach 2 meters long. They leave their home and migrate thousands of kilometres from the fresh water to the sea water into the Pacific Ocean to release eggs and sperm in a process called spawning. Their eggs hatch far in the South Pacific Ocean near Tonga. They are very small and can only be seen using a microscope. The fertilised eggs then develop into larvae called leptocephali, which travel back to New Zealand drifting via ocean currents over 9-12 months and eventually arrive in New Zealand. Eels then enter our rivers as small juveniles that are known as glass eels. They are about 60-75 mm long. After several weeks in the fresh water the darken an become known as an elver. They migrate upstream during the summer. They are able to climb obstacles until they get to 120mm length. - niwa.co.nz/life-cycle

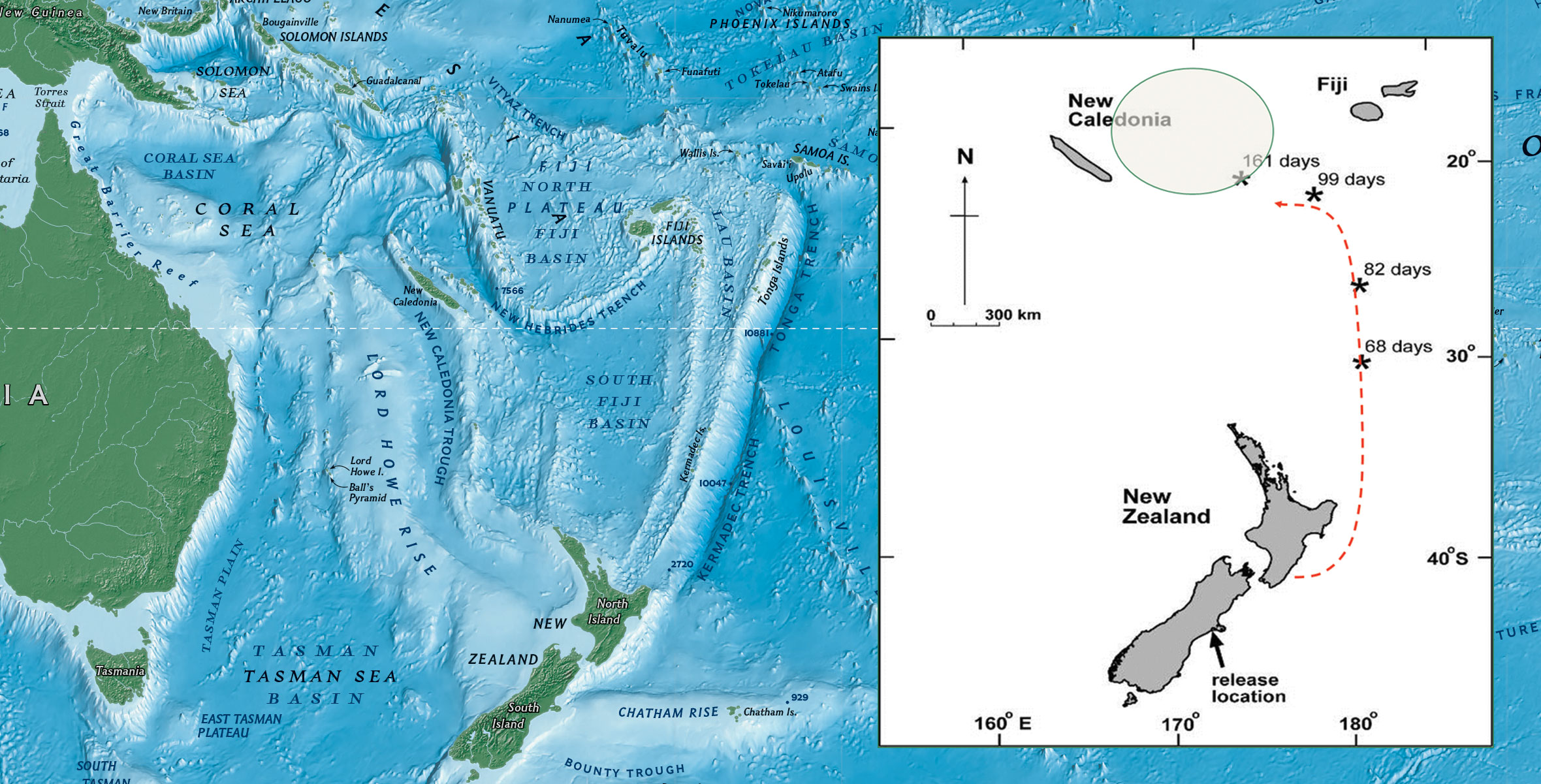

ABOVE: Map of the pacific ocean and "ring of fire" showing the edge of the techtonic plate that forms the Alpine Fault line in New Zealand, and the Kermadec and Tonga Trench's. The Kermadec Trench is one of Earth's deepest oceanic trenches. Every year, a proportion of eels mature and migrate to sea to spawn. Downstream migrations normally occur at night during the dark phases of the moon, and are often triggered by high rainfall and floods. National Geographic

Location of archival pop-up tags ascent locations on four longfin eels tagged and released from south of Christchurch. The tags were programmed to release from each eel at a different time. Once the tags came up to the ocean surface they sent all of the data they had been collecting via satellite to NIWA scientists eagerly awaiting the results. Credit: Don Jellyman

'Ka hāhā te tuna ki te roto; ka hāhā te reo ke te kaika; ka hāhā te takata ki te whenua' - If there is no tuna (eels) in the lake; there will be no language or culture resounding in the home; and no people on the land; however, if there are tuna in the lake; language and culture will thrive; and the people will live proudly on the land - Nā Charisma Rangipuna i tuhi

They are legendary climbers and have penetrated well inland in most river systems, even those with natural barriers.

Elver eels wiggling their way into Lake Opuha via the Elver Bypass 2023. Photo's Supplied by Opuha Water Limited (OWL)

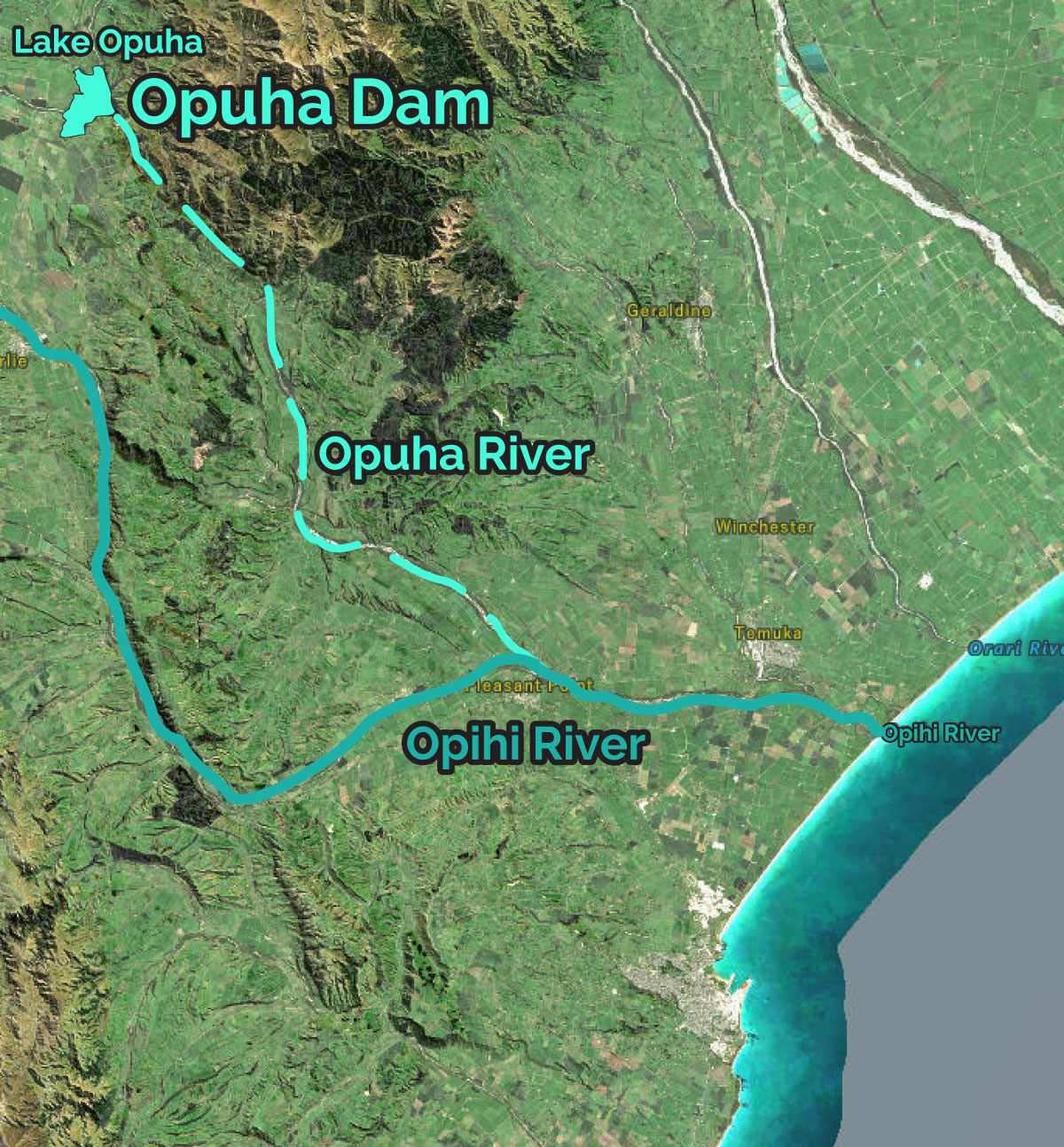

Elver bypasses on the Opuha Dam infrastructure ensure tuna/eels can continue their migration up the Opuha River into Lake Opuha. Here you can see little Elver (juvenile tuna/eels) at the Opuha Dam. They wiggle their way up the elver bypass, a special pipe which runs up the side of the 50m high dam from the Opuha River, and drops down the other side into the lake.

Elvers migrate upstream, typically between late November and early March, when temperatures reach about 16°C. They are able to climb damp vertical surfaces until they are about 12 cm long, at which size they are too heavy to stick using surface tension.

Most high dams in New Zealand are now equipped with bypasses, eel ladders and/or have trap and transfer operations. What is reasonably uncommon in NZ is monitoring to understand the effectiveness of the bypasses. To help fill this gap in knowledge, Opuha Water Ltd (OWL) are currently doing some small modifications to the elver bypass boxes to enable their team to temporarily catch and count how many elver are going into the lake.

OWL doesn't have a mechanism to provide for adult tuna to migrate downstream but are actively pursuing opportunities to establish a trap and transfer programme, whereby adult eel are netted and transferred downstream below the dam where they can then migrate out to sea.

Above: The Lake Opuha Dam was built in the late 1990's. Lake Opuha is a 700 hectare man-made lake, built as an irrigation reservoir as an infrastructure project undertaken by the community of South Canterbury. The Opuha Dam, (where the North and South Opuha Rivers meet near Fairlie), also generates electricity before water flows on to meet the Opihi River further down stream.

As well as the increased value of the farms and the farming activities, the reliable irrigation has provides growth for various vegetable processing exporting operations in Washdyke and has supported the growth of the massive dairy processing facility at nearby Clandeboye.

The 7MW power station contributes to the local electricity network and the revenue from the electricity sales accounts for approximately half of the company’s income.

In this map you can see the Waimataitai Lagoon before it was drained and turned into a park. The stream was piped underground and can be seen at the golf course. Miscellaneous Plans - Borough of Timaru, South Canterbury, 1911 - T.N. Brodrick, Chief Surveyor Canterbury ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/IE31423732

Above you can see the stream that runs past Timaru Top 10 Holiday Park. This runs under Ashbury Park to sea. The park used to be a large tuna weir. "Waimātaitai was a hāpua (lagoon) renowned as an important source of mahinga kai. In 1880 Hoani Kāhu from Arowhenua described Waimātaitai as “e rauiri” (an eel weir) where tuna (eel) and inaka (whitebait) were gathered. This saltwater lagoon was eventually lost in 1933 due to changes in sediment drift caused by the creation of the Port of Tīmaru." - kahurumanu.co.nz/atlas

What was once a lagoon, is now Ashbury Park. Aerial view of Timaru, showing Caroline Bay, harbour and town between 1920 and 1939. - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections FDM-0690-G

This 1874 sketch is from Benvenue Cliffs looking to Dashing rocks. You can see the spit that used to be here and the lagoon on the left. Eliot was here taking measurements to draw the Harbour construction plans. After the breakwater was started in 1878, it was noticed that the shingle bank was being eroded. In the early 1800s, basalt rock was brought in to protect the bank and the rail way behind it. By the 1820s the lagoon was under threat, it was filled in and by 1935 the Waimataitai Lagoon was gone.

- Eliot, Whately. 1874, Near Timaru, N.Z., Sept. 23, 1874 , viewed 27 April 2023 http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-138582026

Tuna / eels in the steam that runs beside the holiday park. This stream connects to a underground drain under Ashbury Park, Waimataitai Beach. Photo Supplied by Timaru Top 10 Holiday Park

Niwa has published an climate report "Understanding Taonga Freshwater Fish Populations in Aotearoa-New Zealand" here: https://waimaori.maori.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Understanding-Taonga-Freshwater-Fish-Populations-in-Aotearoa-New-Zealand.pdf